TRUE STORY :: It is remarkable how long Aaron, a 36 year old tech savant, was allowed to stay in his Toronto apartment, after he lost his roommate and couldn’t make rent solo.

Nine months, until Aaron’s luck finally ran out and he was evicted, at the end of January, 2022.

By then, Aaron’s mental health had taken a beating. Covid had done a big number on it, like it did countless others, and he had months-before been diagnosed HIV-positive; he couldn’t work and was receiving financial assistance. He was far from a healthy mental space as he raced to find a new roommate. As efforts to find one failed, with eviction looming, his clinical anxiety became an overwhelming struggle that hindered him, to the point of paralysis.

You can’t make things happen if you can’t breathe, and if your monkey-mind is racing with what-ifs. Aaron became a shut-in, leaving only occasionally to hit the convenience store downstairs for cheap food.

“I didn’t want to go out,” he says. “I was afraid. I believed if I left my home, I wouldn’t be able to come back to it. It’s not rational but it’s how I felt.”

That dreaded moment - for him to leave and never come back - manifested.

Aaron could barely function the day-of. He says he was in shock and disbelief, even though it was no surprise. It took everything within him to get some of his valued possessions into a storage locker he couldn’t afford, leaving most of his belongings behind in the apartment - where was he to move them to?

With two knapsacks filled with necessities like his laptop, phone, chargers, and a couple changes of clothes and toiletries, Aaron began his new life, officially unhoused.

“I was left in the building lobby with my coat, knapsack, my medications and a stuffed animal from my childhood.

“Eventually someone called the police because I was just sitting in the lobby; I didn’t know what to do. The police let me go back and grab more of my things.”

To be unhoused is anyone’s nightmare, yet in the beginning Aaron managed himself exceedingly well, to my eyes. I spoke with him, and saw him a lot in his early days of no fixed address. I would’ve been a hot glue gun mess. He was calm, accepting, optimistic, and going with the flow. He was strong. I marveled at his positive headspace.

“I was going a little bit crazy because I thought I heard someone cock a gun and so I left.”

Aaron first stayed with his uncle - under the condition Aaron actively look to solve his problem. He did, reaching out to organizations meant to help, like Fife House, and the Toronto People with AIDS Foundation. He was added to a housing list, told it could be as long as nine months before housing became available (in a city as rich as Toronto, in a country as rich as Canada; we sit at #9 in the world ranking of economies; the International Monetary fund predicts Canada be the fastest growing economy in G7 in 2025.)

Living with his uncle didn’t last. There were renovations scheduled where Aaron had been staying, two months into his time there. Fortunately, Aaron’s best friend took him in. Aaron stayed in a space in the basement. But before long, his friend’s girlfriend wasn’t into it. Aaron’s bestie felt badly, and so bought Aaron Air B&B credit, enough to last a month. Aaron was appreciative and in good spirits when he came by mine, to stay a couple days while he searched for space fitting his budget. He was, still, remarkably together. I remained impressed.

Aaron’s choice of Air BnB turned out to be a small bedroom in a house full of one-rooms in the west end of the city.

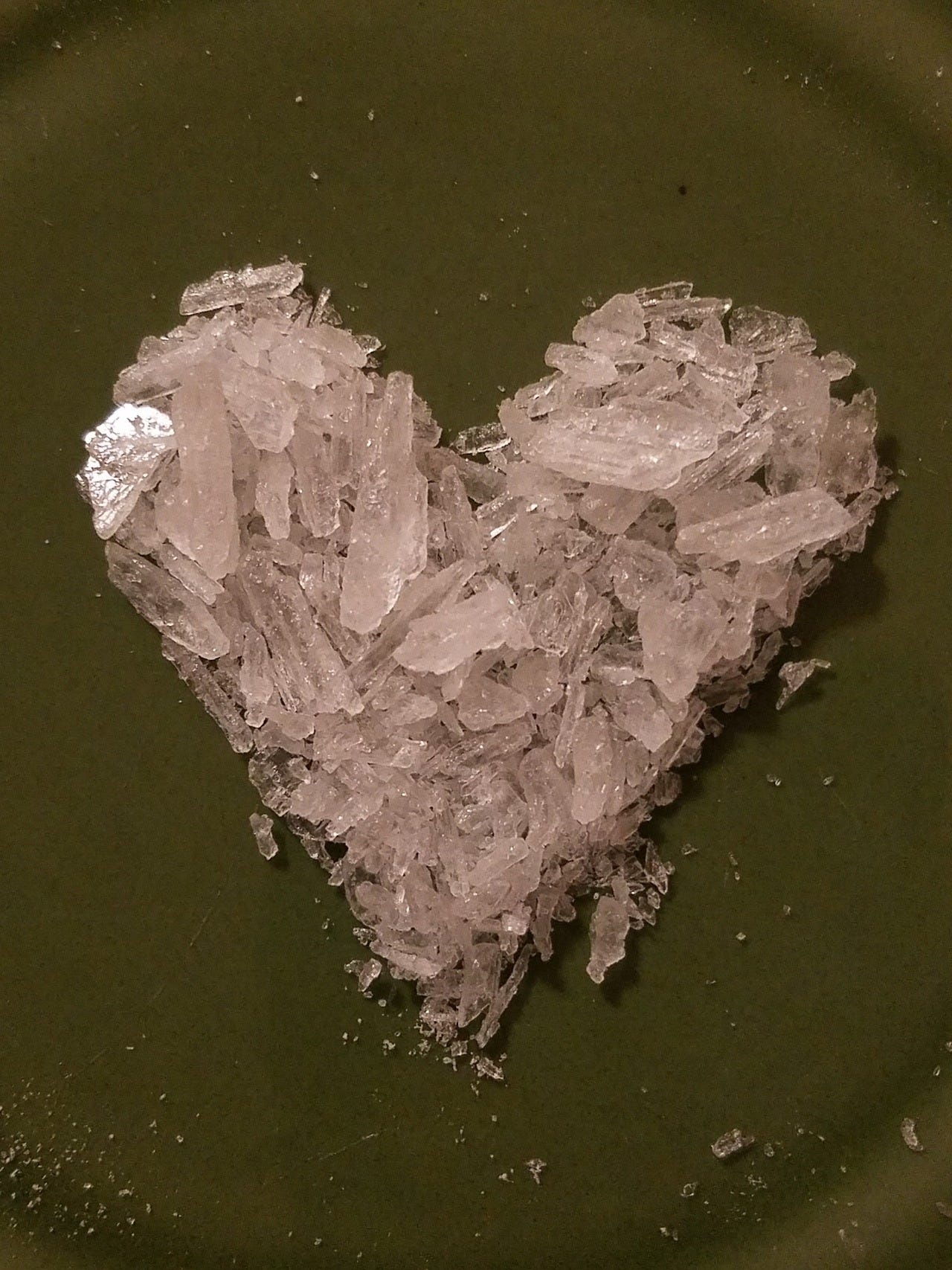

“I think this might not be the best place for me,” Aaron texted me a couple nights after he moved in. He shared he had seen different women entering and exiting the building - in the same dress - that he was hearing sex noises all the time; that people were in and out at all hours; and how he heard the sounds of someone crying from above. And the people above him didn’t seem to be able to keep hold of their crystal meth pipe; Aaron, having lived experience with the drug, knew the distinctive sound of when one dropped to the floor above his head.

It had been a while since Aaron had slept properly; I noticed at my place his sleep was sporadic. I also knew he’d been fleeing the fresh hell of his situation, reaching for relief through partying when friends offered him meth as escape. If you’ve been up for a couple of days, one of the first responses from your body is auditory hallucinations. So, the sex noises… the sound of a meth pipe… people crying… Was that real, I wondered, or was Aaron in dire need of shut-eye?

“This is when I think my psychosis started,” Aaron recalls. “I was starting to be paranoid, hearing things.”

His month at the allegedly sketchy Air BnB ended after what felt like a week. Once more, a broke Aaron was back to being unhoused. Going to a local shelter was out of the question. Toronto’s shelters are violent, rife with theft, and anyway, Aaron couldn’t get into one - they were all full.

But, Aaron is gay - gay men are resourceful. He did what so many gay (and some straight) homeless guys have done before him: he hit the sex hookup sites, and apps, like Grindr. He hooked up, so as to have a roof over his head at night.

There was a problem. When you connect online, the guy expects you to arrive and… shag. Not curl up and sleep. Not be fed. You are expected to have sex. And often, almost exclusively in Aaron’s experience, the guys he’d meet up with were PnP-ing (party '‘n’ play: using recreational drugs to enhance their experience.)

Now Aaron found himself in situations where he was getting high more than ever - usually on meth, and often GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate, which produces feelings of euphoria, relaxation and sociability, and an increased sex- drive) just to not be sitting on a park bench, or wandering the streets all night.

While it was a temporary vanishing act from his problems, partying left him more sleepless.

By this point, I wasn’t questioning. Aaron had entered meth psychosis.

He stayed at one trick’s - Robert’s (not his real name) - for several nights in a row. They partied each night non-stop. I got texts.

“Robert had someone over. I was in another room and I could hear them talking. And then when I’d go out, there was no one there. And Robert said he didn’t have someone by. But I heard him. Why is he lying to me? I don’t understand.”

My heart sunk. The remarkable, keeping-it-all-together Aaron was gone.

Another text another night: “I was going a little bit crazy because I thought I heard someone cock a gun and so I left.”

Left without keys, stuck outside overnight.

Eventually, Robert asked him to leave, telling me later there’d never been anyone else in the apartment, and certainly no gun.

Besides hooking up, bathhouses were sometimes another option, when Aaron would be given the odd free complimentary entry pass.

Same problem though: drugs and all-nighters.

More texts: “My ex-boyfriend, I can hear him in the hall.”

“Johnny is here and he’s laughing at me.”

You don’t tell a person in psychosis that you don’t believe them, so I tried reason when I texted back. “So what if your ex is in the hall? He’s allowed to be at a bathhouse. Johnny’s allowed, too. So what if you hear him laughing, it could be about anything.”

At one point he thought the house music playing was telling him things. “It was as if someone were trying to send me a message.”

Fucking hell.

From inside his small dark room at the bathhouse, Aaron’s anxiety amped, and paranoia would keep him locked in there, alone with his psychosis.

Bathhouses and hooking-up were now no-gos.

He would come over, and I’d try my best to ground him in some kind of reality, doing what you’re not supposed to: I told him I didn’t believe him.

“But,” I would ask, “do you trust me?”

“Yes.”

“Then trust me now, as your friend, Aaron: You aren’t getting any sleep. You are under tremendous stress not knowing where you are staying, every night. You’re partying. So your mind is now playing tricks on you. I’m not saying you don’t hear what you hear; I know you’re hearing it. But I guarantee you 9 times out of 10 what seems real isn’t. It’s psychosis. I wish you could just go somewhere and sleep for a week.”

He stayed at my place for a few days. I threw his dirty laundry in the wash and ordered us food; Aaron had lost an enormous amount of weight. He talked a lot. It often didn’t make sense. This became challenging to witness. Despite being at mine - where we usually sleep at night - he couldn’t relax enough to fall into the deep slumber I knew his body craved. He would hold his head above the pillow, like he was on guard, ready to snap back alive if need be, waking up, muttering something, drifting off.

After a few days, I needed my home back. I had friends coming for dinner that night, and an out of town friend was coming to visit the next day, to whom I’d promised the couch for a couple nights.

I hated kicking Aaron out, and felt guilty, but I couldn’t accommodate him longer than I had; asking him to leave left a knot in my stomach. His psychosis was raging.

Then I stopped hearing from him.

He didn’t return my texts or calls.

I worried.

I did some digging and learned his parent’s names, emails and phone numbers out in Nova Scotia. I knew Aaron could be angry with me for reaching out to them, but if I didn’t hear back soon, that was my intention.

Out on the streets, where he would experience three nights with nowhere to go, Aaron’s life became the stuff of nightmares. He was now convinced people were after him and began to hide from “them.” He believed his belongings were bugged.

He hid in the delivery area of the Eaton Centre. “Then I ended up at the (nearby) Church of the Holy Trinity,” Aaron recalls. There, he ditched his knapsacks containing his worldly possessions. He thought a friend would come get them for him, that friends would come and help him.

Eventually he made his way inside the Eaton Centre. “I was sitting on the floor in the mall, security came and asked me to leave. I said I wanted to go to CAMH (the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Canada’s largest mental health hospital) and they said they’d call an ambulance. Eventually, after about 20 minutes, according to Aaron, the security guards told him CAMH was really busy, so he’d need to walk there, something that would take hours.

Details of what happened next are sketchy, pardon the pun. Aaron ended up in a parking garage, he doesn’t remember where. A security guard found him; Aaron recalls him being very nice. Then, he was sleeping on a bench by the famous TORONTO sign at City Hall. Another security guard got him a Coke and watched him for a couple of hours. Then he hopped onto the TTC - Toronto transit - without paying, with the intention of going to his uncle’s. But he kept falling asleep, missing his stop - it took six hours to get to there.

It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like seeing Aaron show up at your door, disheveled, in psychosis, but that’s how Aaron arrived at his uncle’s place.

“I want to go to CAMH,” he told him, and so his uncle drove him there.

Days later, back at mine, I still had no idea if Aaron was okay. As I was about to call Aaron’s parents, his mother called me. They had been notified about Aaron and were en route from Nova Scotia to come pick him up and bring him back there. Aaron, knowing I’d be worrying, gave them my number. That’s when I learned he had been at CAMH for several days. They’d given him a shot of an anti-psychotic, and other drugs to get him to the point of being able to detox.

I went to see him. It was an experience that left me jangled. I was happy to see a cleaned-up Aaron, sober, who had slept and was medicated, but he was surrounded by people not in the best of mental states, to understate. Of course, but I’d never witnessed anything like it, it was terribly sad. My city has a serious mental health crisis going on, especially since Canada’s infamously long pandemic lockdowns.

It’s been almost two years since Aaron was moved to rural Nova Scotia with his family, where he is welcome to stay indefinitely. He has a dog now. The family goes for walks by the sea and spot seals.

“I’m in a much better place,” Aaron, now off drugs and with no access, reports. “I was in a spiral I could not pull up and out of. I feel a lot better and never want to have that experience again. It’s easy to get into homelessness, and it’s hard to get out of. And to not be able to trust your own thoughts or memories is horrible. I’m a logical person and looking back to how I was thinking, it’s hard for me to reconcile that with how I really am. ”

He hasn’t thought much about the future, saying he is still healing.

We stay in touch. He feels isolated (Halifax, the closest city, is 90 minutes away and there are no taxis or Ubers where he lives.) He misses gay people, Toronto, and having friends. (Aaron is possibly the only gay in the village, for real.)

At a recent dinner party I attended, the subject of homelessness arose. One woman, in her 80’s, who lives a very comfortable life and has never worried about money for most of it, said: “But you have to ask, what were they doing before they were homeless?” saying aloud what I believe many think: How do the unhoused bring this on themselves?

Most don’t though, and I understand this more clearly than ever, having witnessed Aaron’s descent first hand. This all began because he couldn’t find a replacement roommate, something that could happen to anyone. Just like losing a job, current sky-high cost of living, having a business go belly up, falling ill, losing financially in a divorce, family violence, sexual or emotional abuse, being kicked out for being gay, or a global pandemic that destroys your livelihood could happen to almost anyone.

Those playing a blame game make the problem worse through their ignorance. Aaron’s experience further grew my respect for those who survive on the streets, seen here everywhere you turn, or in the countless encampments that fill my wealthy city, where condos few can afford are erected seemingly on the daily, sports stadiums get untold millions thrown at them for renos, and where we’re now talking about spending billions on a bridge to connect cityside to the Toronto Islands.

According to Homeless Hub, the number of homeless in Canada ranges from 150,000 to 300,000, and that doesn’t include the hidden homeless, those living with family or friends. In Toronto, it is estimated there are more than 8,000 people experiencing homelessness.

Canadians who judge and blame should get educated and stop. Each of us should be ashamed of this crisis society has allowed to happen, and we should get our act together, and help those who need it most. Elected officials should be hearing from us on the daily. Aren’t you tired of seeing fellow humans passed out on the street or living in tents?

This issue and our views about it are so tragically ass backwards - and very few end up as lucky as Aaron did. It’s time we stopped looking at homeless people like they’re transparent nuisances, who did this to themselves.

Hear The Shaun Proulx Show every weekend on SiriusXM Canada Talks 167. Hire me to speak or host your next event. More info: shaunproulx.com

Far too many people I know are ending up in this situation. It’s heartbreaking to see and there is so little I can do for them. Aside from providing occasional shelter and hot meals , it’s overwhelming to see just how little it does to resolve each persons ongoing struggle.

Thanks for writing this. It’s a serious issue that is getting worse each da. Compassion , willingness to help and be voice at the time we choose our municiplevrepredrntstives is more critical now than ever.

Thanks for this familiar story, written with empathy and compassion.