SLICE OF LIFE :: Tessa (who isn’t using her real name so she could speak freely) is a striking woman. Tall, lithe, with shoulder-length blonde hair and kind eyes that sparkle - if she told you she was an actress, you’d buy it. She looks much younger than her 60 years, and is a divorced mother with two grown children, a son and a daughter.

In 2020 she retired from her previous career to begin anew doing something utterly different: she’s a humanitarian aid worker (we aren’t naming the organization Tessa works for, again so she can speak openly.)

Tessa is not long back from Gaza, and is still overwhelmed by the absolute devastation she bore witness to. Camps by the sea, bombing daily, everything we hear about daily on the news, magnified a thousand-fold when witnessed in real life.

“An experience beyond words,” she says with sadness in her voice.

When she had to suddenly leave Gaza because of a family medical emergency, she had with her just one security detail to accompany her. Typically, aid workers travel in groups (safety in numbers.)

When they got to the Israeli border, immigration officials would not allow her security to continue with her. At gunpoint, he was told to leave. Tessa had to make a split second decision as to whether or not she should continue on alone, or stay in Gaza where at least she’d still have her detail by her side. She decided she would go solo. Her detail gave her his phone, so she’d have something to communicate with, in case she had to.

What should have been a quick turnaround in Israeli immigration was not. Tessa found herself taken into isolation, kept in a concrete compound for 3 hours. Immigration said they identified the body wipes in her suitcase as a possible component for bomb making. Eventually, they acquiesed and let her through. She still feels the issue they made was all a crock.

She was also in Yemen this year, springtime (“Never go to Yemen,” she texted me. “Not safe for you.”) Not safe at all for gay people, and with a heavy societal pressure for women there to cover themselves completely. Tessa also had to be fully covered, however she was allowed to show her face. She wore a hijab, to cover her hair, and an abaya, the common, simple, loose over-garment to cover her body. While conducting the training she facilitates on her missions, she noticed a startling phenomenon: she was engaging in conversation almost exclusively with women who weren’t fully covered, basically ignoring women who were.

“Having everything hidden but your eyes voids you,” she realized, and had to make an extra effort to engage with covered females, who, she noticed, also typically said far less than everyone else.

The point of all the covering - making women invisible - almost always works. Something else magnified a thousandfold when she experienced it first hand.

Tessa traveled from one end of Yemen to another. It’s a country divided into two distinct entities, south and north, with two different governments and with two different visas needed to go from one part to the other. North Yemen is run by the Houthis and is more extreme, especially for women, for their movement, and their ability to be part of civilization. The Houthis are a rebel group who have taken over North Yemen and are unpredictable. Check points are also points of high risk, you have no control. Risks in south Yemen come from the protests and uprisings taking place there.

Once you are held captive, you could be kept for a long time. Ransom and political negotiation both move at a snail’s pace. Days, months, years could pass…

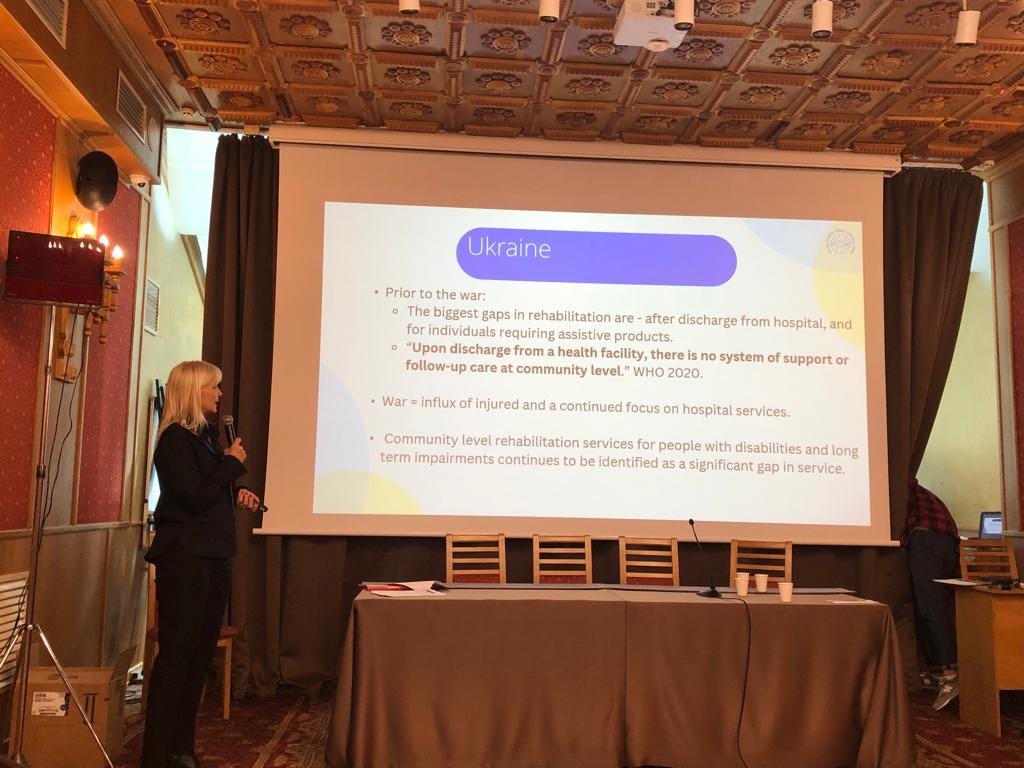

In Yemen, you found out you were being bombed because you heard it. However, Ukraine, where Tessa has been stationed more than once since Russia invaded it, has good technology; there’s an app for that. (Orange alerts mean take cover.) When Tessa first began a mission in Kiev, Russia was attacking their infrastructure, causing her and her colleagues to often heed their apps and shelter. Other times they spent working by mere candlelight.

On that mission, she grew a dark, sad skill: the ability to differentiate types of mines by the kind of injury a wounded soldier came in with after stepping on one. Having your leg blown off right below the knee - while your arm right below the elbow was also taken out - came from one very specific mine, for example. “It was gut wrenching to see a specific injury like that - and to know,” she says.

A while back, Tessa was in Somalia. There, she was walking down the street with an Ethiopian colleague, covered, but not properly, a no-no. Also forbidden: as a female she was breaking cultural norms by walking with a male who was not a relative. Two men who spotted these egregious errors identified themselves as immigration officers when they approached her, asking to see Tessa’s documents and visa. Tessa had her passport, but her visa was back at her hotel. The officers told her to get into their car. She had the wherewithal in that red hot moment to listen to her gut, which told her to stand up to them and refuse. She said if they wanted to see her visa, they had to walk with her back to the hotel, where there was much security all around. She was not getting in their car. So they walked. Once at the hotel, she showed them her visa, and any trouble ended there.

But things could have gone another way. The alleged immigration officers telling her to get into their car could have been the first move in something that can happen to Tessa and other humanitarian aid workers like her on any given mission in any hostile environment: kidnapping.

Tessa is trained on what to do if she’s ever kidnapped. Not kidnapped in your own national country, like something out of a true crime podcast, but in hot spots like the ones Tessa spends much of her time in.

There are three types of kidnapping, Tessa says. The first is to hold you for ransom. The second is because you are now part of an extremist group statement. The third type of kidnapping is to keep you as part of a political exchange: hostage for hostage.

Once you are held captive, you could be kept for a long time. Ransom and political negotiation both move at a snail’s pace. Days, months, years could pass, and so it’s important you don’t hold the false hope that the experience will be over quickly. It likely won’t be.

It’s likely you will be raped, whether you’re man or woman and you should accept this fact. Male captors rape their male prisoners to demonstrate their power over the kidnappee.

Your main goal in all 3 types of kidnapping is to stay alive, however each type carries different odds of survival.

Tessa has, obviously, thought about possibly being killed doing this dangerous work.

Staying alive is most difficult if you are kidnapped for reason number 2, political statement. Your odds of living are very low. The kidnapper’s very intention is to kill you to make a political point; there is very little hope. Here, try to be as invisible as possible. Don’t speak up. Sit in the back, be gray, blend in. Don’t look your captors in the eyes, look down, appear small, and don’t do stupid things like be defiant. Don’t be the first person they think of, in other words, when it’s time to commit murder.

Your best chances of survival is number 3: political exchange. Here is the greatest likelihood you will be kept alive and released, for you are a bargaining chip.

If number 1 is why you’ve been kidnapped - ransom - you may be kept alive but you may not be let go. Instead, if ransom negotiations fail, you may find yourself sold. Trafficked, to put a finer point on it.

In both 1 and 3, disassociate from the whole experience. Disassociation is a way to be able to manage the kidnapping trauma long enough to get out on the other side, to your real life, with more of your mental health intact. To disassociate, give yourself an alternate persona, a nickname. When you talk to yourself, speak instead of your other persona. If you’re calling yourself Bobby, you might say: “Bobby had a good day today, no one hurt him.” Alternatively, if something bad happened, it happened to Bobby. Bobby becomes the person who has the kidnapping experience, not you.

In both the 1 and 3 types of kidnappings, try to humanize yourself. Be pleasant, speak to your kidnappers. It makes it harder to kill you if they develop any kind of small tie to you as an actual person and not just see you as a commodity. Ask careful, small questions, perhaps about sports, or their family. Do as they ask. Do not cry, beg, or plead. This just puts you in the category of being annoying and makes you an easy choice when it’s time to get rid of someone. Ask for small things: a wash cloth. A pen and paper. If you can get your captors to start bringing you things, it goes a long way. When we bring something to someone who wants it, we are taking care of them, and so doing this will form a small connection with your kidnapper, who might make the choice not to kill you.

To maintain your mental health, eat and drink any time you are given food and water, even if you don’t want to or don’t want it. Try to exercise, in any small way, and if you can, bathe. Any kind of self-care you can give yourself will go a long way to keeping you remaining stable and strong.

Learning of such kidnapping tips ‘n’ tricks was a slap of reality, Tessa says. Does it make her feel more fearful, that slap? “I don’t feel more scared, I feel more prepared,” she says. “I’m more situationally aware.”

Having to be so cognizant does have drawbacks,however, including a constant, underlying low level of stress. Coming out of Yemen, for example, she realized she was exhausted from having to be so hyper-aware the entire time.

Tessa was readying to go to Afghanistan next, but that mission has been cancelled. She’ll return to Gaza soon, and come back home to Canada for the holidays.

Wherever she goes, she’ll stay in compounds or gated houses, mostly concrete structures. She’ll have security and a driver but need permission to leave before going anywhere. Restrictions on movement are heavy.

When she first began this later-life career, her children were both understandably worried. Now they’re more accepting that this is her path, but their concern goes up when she’s in a more volatile situation like Gaza.

Tessa has, obviously, thought about possibly being killed doing this dangerous work. She says she is at peace with the fact she’s led a great life, and knows the risks she takes are high.

She cops to being an adrenaline junkie. “Definitely I am addicted to the adventure,” she laughs. “I’m not one that easily settles into a routine life. I love this work because there is change, and adventure, and I get to experience beautiful cultures and meet fascinating people from all over.”

Fascinating people, like Tessa herself, who follow their passion in a quest for a rich, satisfying life, no matter how harrowing or dangerous a journey they have to take in order to find it.

Shaun Proulx hosts The Shaun Proulx Show heard weekends on SiriusXM Canada Talks 167. More at ShaunProulx.com